Last week, I had the privilege of attending a screening of Johan Grimonprez’s powerful new documentary “Soundtrack for a Coup d’Etat” at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, as part of the San Francisco International Film Festival.

The film, which traces the story of Patrice Lumumba, the visionary first prime minister of independent Congo, left an indelible impression on me, given my long-time fascination—some would say obsession—with Lumumba. I appreciated Grimonprez’s ambitious, kaleidoscopic portrait of the leader and the independence movement he lost his life for, but I also appreciated how the film, and Grimonprez’s pre-screening conversation with musician, author, and Professor Fumi Okiji, kept me thinking long after I’d left the theater about where Africa found itself in 1960… and the many eerily similar challenges it faces today.

The film is roughly chronological but not entirely linear—which only seemed appropriate for the Belgian filmmaker, who before the screening received SIFF’s Persistence of Vision Award, which annually honors a filmmaker whose work falls outside the realm of narrative features. And to tell such a complicated story as Lumumba’s requires a prismatic approach. The film follows the concurrently unfolding, constantly swirling stories of Lumumba’s career, the Congolese independence movement, and the growth of Pan-Africanism, set against the shifting geopolitical dynamics of the postwar world. And then there’s the music—more on that storyline in a minute.

Through masterful deployment of archival footage, audio recordings, and literature, Grimonprez brings to life the promise and tragically short-lived triumph of Lumumba’s vision for a united, prosperous Congo. The filmmaker puts Congo’s struggle in a continental context—Nkrumah and Ghana’s first steps toward independence and the United States of Africa are featured. Then, Grimonprez goes global, examining how Western powers, determined to maintain control over the Congo’s vast mineral wealth, baldly manipulated its independence movement. He also puts the United Nations under a microscope as an instrument of colonialism under a new guise, and breaks down how young African nations became pawns in the Cold War—there is remarkable footage of Khrushchev, Castro, and their complicated engagements with African leaders.

The film spans from the 1950s until after Lumumba’s death, but it is the June 30, 1960 declaration of Congolese independence and the months that follow that hold the film’s attention—and gripped mine. This was, I’d argue, Africa’s sliding door moment, when things could have gone in the right direction for the African people. Independence was spreading, Pan-Africanism was being championed across the continent. Instead, everyone soon discovered their dreams of independence were an illusion—a new sheriff was in town, but carrying the same old colonial baton. What happened in the Congo is but one story, though you could argue that the Congo is a proxy for many resource-rich but under-resourced African nations during this era and up to the present day.

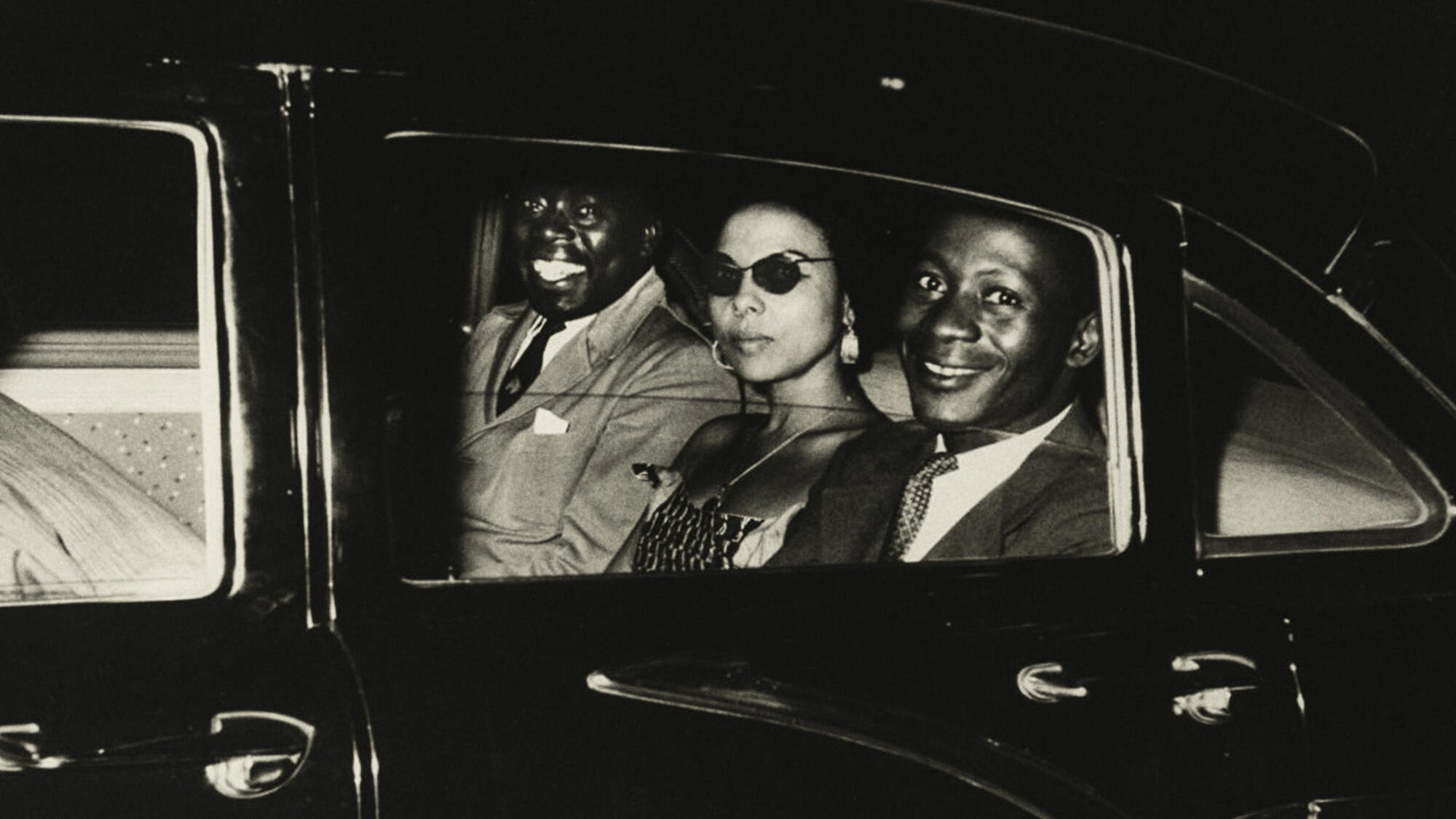

But what about the soundtrack of the title? Grimonprez’s storyline is driven by a haunting soundtrack featuring African jazz greats like Joseph Kabasele (Le Grand Kallé), whose iconic “Indépendance Cha Cha” became an anthem for African liberation. These musicians are paired with the music of prominent African American jazz artists like Louis Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie, who were strategically deployed by the U.S. State Department as cultural ambassadors during the Cold War era to promote democracy abroad.

While the music of these artists symbolized freedom and resistance, Grimonprez calls attention to the contradiction embedded within. American jazz musicians were sent as goodwill ambassadors to regions where the US was covertly, concurrently stifling emerging democracies—hardly a song of freedom. And of course, resistance had its limits for Black musicians, as, once they returned home from their goodwill tours, these same artists faced profound racial discrimination in America. In 1974, singer Nina Simone, also prominently featured in the film, was so disappointed with the lack of progress in the US Civil Rights movement, that she moved to Liberia (the country of my birth). “The America I’d dreamed of through the sixties seemed a bad joke now, with Nixon in the White House and the black revolution replaced by disco,” she wrote in her memoir.

Taken together, Grimonprez’s deft interweaving of art, politics, and the cold calculus of business interests shed much-needed glare on a critical chapter in African history. I left the theater moved and shaken, but also inspired by the enduring power of art, music, and film to awaken our collective conscience and help light the way forward. I mean that word, forward, because perhaps even more resonant than history in “Soundtrack” was its contemporary commentary. I could not help but note the parallels between the Congo of the 1960s and the challenges facing the Democratic Republic of Congo and much of resource-rich Africa today. Grimonprez restricts his current-day editorializing to a fleeting splice of Tesla advertising, a brief clip of Apple products… and leaves it to the attentive viewer to connect the dots. While the prized resources may have shifted from the uranium that powered the world’s first atomic bomb to minerals like cobalt, lithium, and coltan that power our modern electronics, the underlying dynamics of exploitation and the thwarting of African self-determination remain troublingly familiar.

There are some differences, of course. Today, China has taken a significant lead over the US and other Western nations in influencing the continent’s resource extraction, and Russia is elbowing in as well. But as it was sixty years ago, international influence raises concerns about the intentions and continued impacts of foreign involvement in Africa’s development.

As I drove home from the screening in my Tesla Model 3, listening to Kacey Musgraves’ “Deeper Well” on my iPhone 14 Pro Max, I was struck by the profound irony of my situation. Here I was, directly benefiting from the very minerals that have fueled decades of conflict and undermined democracies in Africa. The unease intensified as “Deeper Well,” a song about personal introspection and searching for a deeper purpose, echoed against my recollections of “Indépendance Cha Cha,” with its theme of African freedom and unity. It reminded me of how our personal quests are deeply entwined with our communal narratives, and how our individual actions impact the wider world. Our lives are bound to those whose resources furnish our lifestyles, even if we don’t see them or the conditions under which they toil. Every product we use, every resource we consume, ties us to the lives and labor of those far away.

But the responsibility cannot only be on the consumer; it is crucial that companies sourcing minerals from Africa are held accountable for their practices, as well. They must ensure that workers are paid fairly, treated with dignity, and provided with safe working conditions. Governments, too, have a role to play in enforcing regulations and promoting transparency, particularly in the extractive industries, on which much of Africa’s economic growth is still heavily dependent. By insisting on ethical sourcing and responsible corporate behavior, we can begin to break the cycle of exploitation that has plagued Africa’s mineral wealth for far too long. International organizations bear responsibility, too, as systems of international aid and development are long overdue for a major rethink and rehaul —in search of solutions that prioritizes the actual needs of the African people, rather than only the narrow interests of a the few, the powerful, and the connected.

There are hopeful signs toward forward movement. Last week, the Congolese government served Apple a cease-and-desist notice, claiming the company uses “illegally exploited” strategic minerals from mines in the country’s east, where it says “human rights are being violated” by rebels. And I recently read a report published by United States Institute of Peace that proposes several critical strategies aimed at building more sustainable and equitable partnerships in the extractive sector. These include encouraging local processing of minerals to add value within African economies, strengthening the rule of law and transparency, and enhancing the involvement of African civil society and media. Of course, the goal of these measures is to ensure that Africa’s natural resources benefit its people first and foremost, provide education, health care, infrastructure, and more. It’s the economic and strategic logic of Lumumba, circling back after seven decades.

“Soundtrack for a Coup d’Etat” is on the film festival and museum circuit for now; with any luck it will be distributed to theaters or available for streaming soon. I’d encourage you to find it, one way or another: the film is a powerful reminder of the profound connection between Africa’s fate and that of the rest of the world’s. Essential to our shared path forward is an honest reckoning with past and ongoing injustices. If you don’t want to go for the message, just go for the music. After a few bars of “Indépendance Cha Cha,” and experiencing the pure joy poignantly encapsulated in that fleeting moment of hope, possibility, and promise for Africa, you’ll also get the message. That is the genius and magic of this brilliant documentary, of Le Grand Kallé’s timeless Africa independence song, and of Patrice Lumumba’s invincible African dream.

This article originally appeared on LinkedIn.